Between 1981 and 2018, The 1%’s Share of Income Surged 100%

Summary:

- Since the adoption of supply-side economics in 1981, wealth inequality has surged, with the income share of the top 1% of earners rising from 10% to 15.5% by 1989, and to 20% by 2018.

- The negative feedback loop between economic inequality and weakened democracy contributes to reduced equal representation and heightened social tension.

- Rising economic inequality has led to health disparities, with the life expectancy of the wealthiest quintile being up to 10-15 years longer than the poorest quintile, according to the Brookings Institution.

- The cornerstone policy of supply-side economics, tax cuts for the wealthy, has aggravated income inequality, exacerbating wealth concentration, and failing to deliver on the promise of widespread economic growth.

Supply-Side Economics: The Theory vs. The Reality

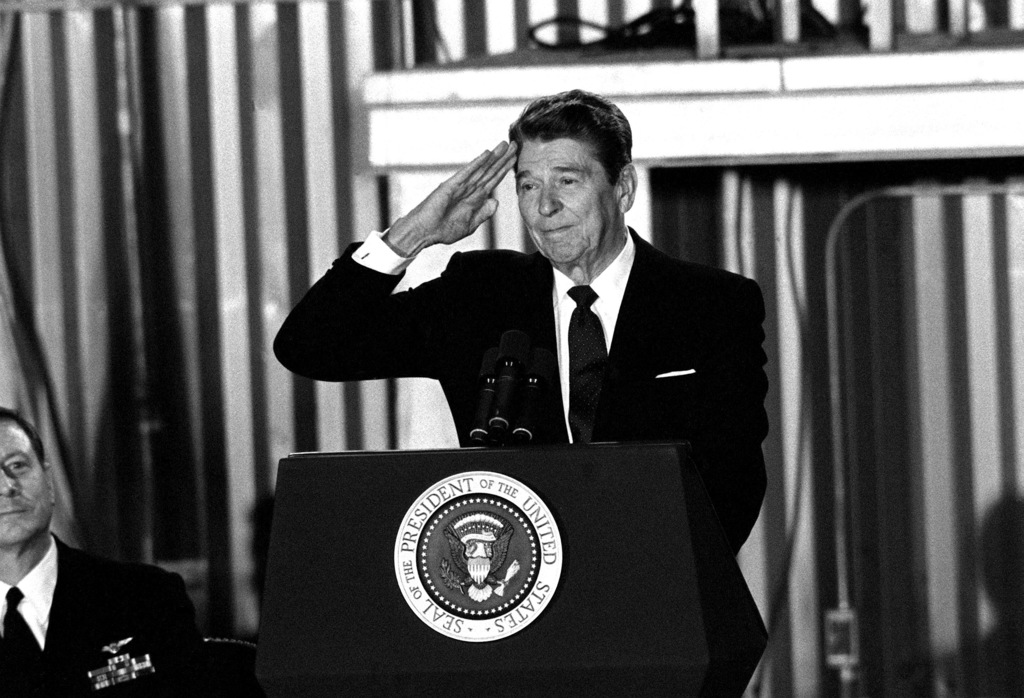

The theory of supply-side economics, first championed in the Reagan era, advocates for economic growth through cutting taxes and reducing regulations. But the economic landscape reveals a stark deviation from this theoretical promise. Instead of generating prosperity, tax cuts have concentrated wealth at the top and amplified economic disparities.

An analysis by the London School of Economics clearly shows the grim reality of this economic approach: “Tax cuts for the rich have failed to stimulate economic growth over the past 50 years.” This has resulted in a jarring accumulation of wealth, with the Washington Post reporting that “the share of total pre-tax income for the top 1% of earners in the U.S. increased from 10% in 1981 to 15.5% in 1989.” By 2018, this figure had risen to a staggering 20%.

The subsequent administrations of George W. Bush and Donald Trump amplified these trends, implementing tax cuts favoring the wealthy over average workers. The Trump administration’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 served as a glaring example. As The Guardian reported, “the wealthiest 400 families in the U.S. pay a lower tax rate than any other income group,” further exacerbating wealth inequality.

The consequences are not confined to the income gap. “Tax cuts for the rich have not led to substantial trickle-down effects,” the London School of Economics found. The anticipated benefits for middle and lower-income groups have failed to materialize, painting a stark contrast between the promises of supply-side economics and its real-world implications.

The Impact of Economic Inequality on Democracy

The wealth inequality perpetuated by supply-side economics poses a significant threat to democratic principles. As wealth disproportionately accumulates among the rich, their political influence swells, undermining the ideal of equal representation.

The Scientific American explains the implications of this phenomenon: “Economic inequality can lead to political instability and social fragmentation”, destabilizing the democratic fabric that binds society. When wealth disparities widen, social mobility decreases, resulting in reduced civic participation.

A negative feedback loop forms, where economic inequality undermines democracy, and weakened democracy, in turn, exacerbates economic inequality. As democracy becomes strained, it fails to check wealth concentration, leading to further economic disparities. As the Scientific American notes, “greater economic inequality leads to an erosion of democratic norms and institutions.”

Moreover, economically disadvantaged individuals often perceive their political efficacy to be diminished in the face of wealth-based power. As The Guardian reports, “people in less equal societies are less likely to feel they can make a difference,” fueling disillusionment and exacerbating social tensions.

The Human Cost of Economic Inequality

The ramifications of supply-side economics extend beyond financial metrics, carving stark lines in the health and longevity of Americans. Economic disparities, exacerbated by these policies, manifest in differing life expectancies.

According to the Brookings Institution, a baby born in 1980 to parents in the lowest income quintile had a life expectancy that was 30% shorter than a child born to parents in the highest quintile. By the 2000s, this gap had increased, with the wealthiest Americans living up to 10-15 years longer than their less affluent counterparts.

These health inequalities do not exist in a vacuum. Economic distress often leads to ‘deaths of despair’ – deaths from alcohol, drugs, and suicide. As the Brookings Institution reports, “deaths of despair have been on the rise since 2000, often concentrated in areas of long-term economic decline or stagnation.”

In addition, life expectancy can dramatically fluctuate within a few miles. As Time magazine illustrates, “in the U.S., there is a 20-year gap in life expectancy based on the zip code in which you live.” These shocking health disparities underscore the social costs of supply-side economics, reinforcing the urgent need for economic policies that benefit all Americans.

For Additional Reading:

- London School of Economics: Tax cuts for the rich

- Washington Post: Tax cuts for the rich

- The Guardian: Trump tax cuts helped billionaires pay less

- Scientific American: How inequality threatens civil society

- Brookings: The growing life expectancy gap between rich and poor

- Brookings: America’s crisis of despair

- Time: Zip code health